How the Arts Festival Began

A great number of arts festivals have been gathering together – alongside the familiar Setouchi Triennale and Aichi Triennale 2016, the new Saitama Triennale and KENPOKU ART got their start in 2016. At the turn of the 21st century, the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale, which started in 2000, and the Yokohama Triennale, held for the first time in 2001, created the opportunity for people to venture out of the art museum, and rather than appreciate the exhibition of modern paintings there, come to enjoy contemporary art in a way that feels more like tourism. In future, the number of festivals may increase even further, as the budget for the promotion of fine arts is settled based on the Tokyo Olympics in 2020. So, in this article, I’d like to take a look back on how these arts festivals got started. Further, based on my experiences as the art director for the Aichi Triennale 2013 and commissioner for the Japanese Pavilion at the Venice Biennale’s International Architecture Exhibition in 2008, I’d like to talk about the present state of arts festivals, in the text to be published hereafter. Then, in the third volume, I plan to discuss the problems facing regional art, as it struggles to stand out in Japan’s already crowded scene.

Tracing the origins of these events, the oldest of them may be the Venice Biennale’s International Art Exhibition. The first was held in 1895, and its participants included artists from 15 countries, such as Gustave Moreau and Arnold Böcklin. That is to say, the event already has a history of over 100 years. It is accordingly the most famous, and has become a powerful brand as well. With the city as host, in the 20th century, the venue at Venice’s sole gardens, the Giardini, was formed to include pavilions for each country, such as the Italian and Japanese Pavilions. As we can see from this style, it was like unto a world’s fair, and indeed, the latter half of the 19th century, in which the first Biennale appeared, was the era of international expositions. London’s Great Exhibition in 1851, the Paris Exhibition, which promoted urban development as it was repeatedly held, the Vienna World’s Fair – at the time, such spaces for new spectacles gained popularity in major European cities, as they brought cutting-edge technologies and products from exotic foreign countries together in one building. We may consider, as a backdrop to this, that in the 19th century, the movement of large numbers of people became possible, including the connection of each city by railroads, and the conducting of group tours.

Furthermore, within the microcosms of the world which were the venues for these international expos, art exhibitions were also held. Baudelaire, who experienced the 1855 Paris Expo and art exhibition, spoke of the necessity of the idea of cosmopolitanism (cosmopolitisme), and began to talk about the concept of modernity (modernité). Through international expositions, it became possible to look not only at one’s own country, but to compare things gathered from various places around the world; the new perspective of contemporaneity also seems to have begun to gain awareness. In any case, if international expos are set as the scene for the beginnings of arts festivals, then it may be natural to associate tourism with them. Now, at the Giardini in Venice, pavilions reflecting the trends of the times were built one after another by architects representing each country throughout the 20th century; they were established as permanent facilities rather than 1-time exhibitions. As for management, rather than have the city manage the venue indefinitely, the later establishment of a foundation allowed a system to be built which would be unable to be swayed by politics and elections, and which could continue long-term. Needless to say, Venice is not an ordinary city. For outsiders, the scenery of the City of Water, with its freely flowing canals, has an extraordinary festiveness even in its day-to-day, and there may be aspects to that which suit the biennale.

Incidentally, aside from art, the Venice Biennale also includes categories such as music, film, theater, architecture, and dance, and its film festival is sure to be familiar, as it appears in news programs reporting on Japanese directors or actors who have received awards. In addition, its International Architecture Exhibition officially began in 1980, in which I’ve participated as an exhibitor, and as commissioner of the Japanese Pavilion. Currently, the International Art Exhibition is held every odd year, and the International Architecture Exhibition in even years. Still, its scale continues to expand, and in addition to the Giardini, where country pavilions stand in line, the Arsenale, composed of former shipyards (about a ten-minute walk from St. Mark’s Square, and a hot spot for tourists), serves as the main venue for themed exhibitions as chosen by the director. At the same time, all sorts of groups and organizations carry out a variety of exhibitions and events in the city while the Biennale is being held. In other words, so many wanted to participate that one venue could not hold them, and now the atmosphere of the Biennale overflows into the rest of the city. In fact, there is no longer any space to build another pavilion in the Giardini.

Brazil’s São Paulo Art Biennial was first held in 1951, beginning soon after the war. This event also employs a system of participation by country. Another event which boasts a long history is documenta, held in Kassel, a small town in Germany, once every five years. Since its start in 1955, it has continued for over sixty years. Here, there are no country-specific pavilions, but rather, large-scale exhibitions based on themes decided by the director. Even in Japan, the Tokyo Biennale, sponsored by Mainichi Shimbun, was held from 1952 to 1970. In particular, its 10th exhibition, “Between Man and Matter” (Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum, 1970), with art critic Yusuke Nakahara acting as commissioner, saw participation from important young foreign artists, including Christo, Daniel Buren, and Richard Serra, becoming a legendary exhibition. However, it was not an “arts festival” as we imagine them today, but rather should be considered to be an “international exhibition” held at an art museum.

Later, as a major development, events such as Korea’s Gwangju Biennale and the Taipei Biennial signaled an upsurge of arts festivals in Asia from the 90s onward. Currently, major cities outside of Europe, including Shanghai, Singapore, Busan, Istanbul, and Sydney, are holding arts festivals, showcasing their cultural identities while remaining conscious of inter-city competition in the era of globalism. In fact, the Yokohama Triennale began in response to such global circumstances, for the purpose of kickstarting large-scale international exhibitions in Japan as well. Under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the independent administrative institution of the Japan Foundation created content for the event, and Yokohama was chosen as the venue, after a search of eligible cities. Incidentally, the Japan Foundation has been involved in the planning and operation of the Japanese Pavilion at the Venice Biennale’s International Art and Architecture Exhibitions, and also conducts business selecting curators and artists when biennales from overseas, such as in Bangladesh, request country-specific exhibits.

At any rate, though the Yokohama Triennale is not a city-sponsored event, and began as a matter of national policy, due to budget screening conducted by the Democratic Party, it became difficult for the Japan Foundation to budget the introduction of foreign artists in Japan (though sending Japanese artists abroad was still possible), and the event has now come under the leadership of the Yokohama Museum of Art. Venice and documenta have come to be recognized as important international exhibitions over 100 and 60 years respectively, but in Japan, whose footing has immediately become uncertain, the question of how to make long-term continuation possible will be a challenge from here on out.

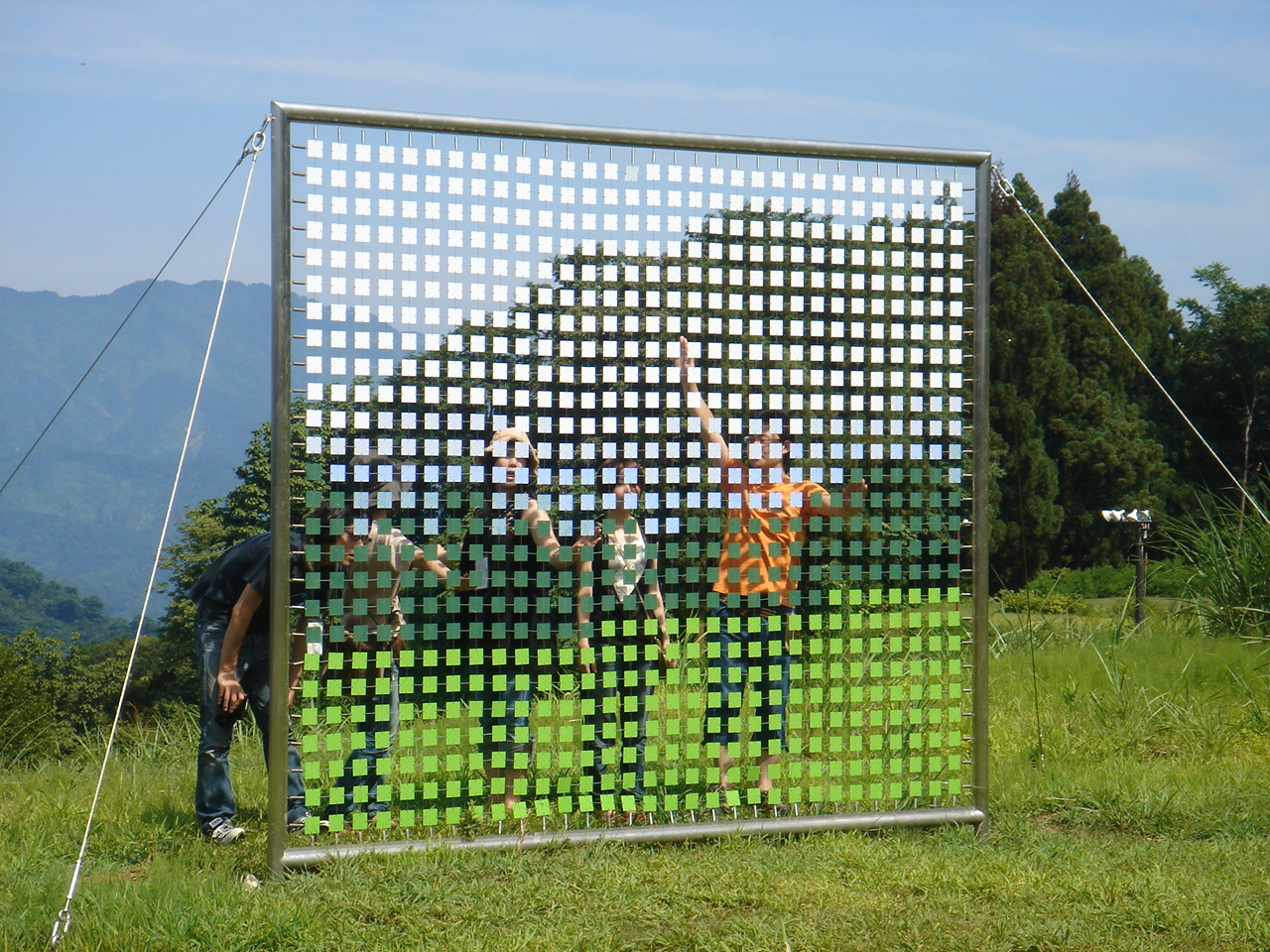

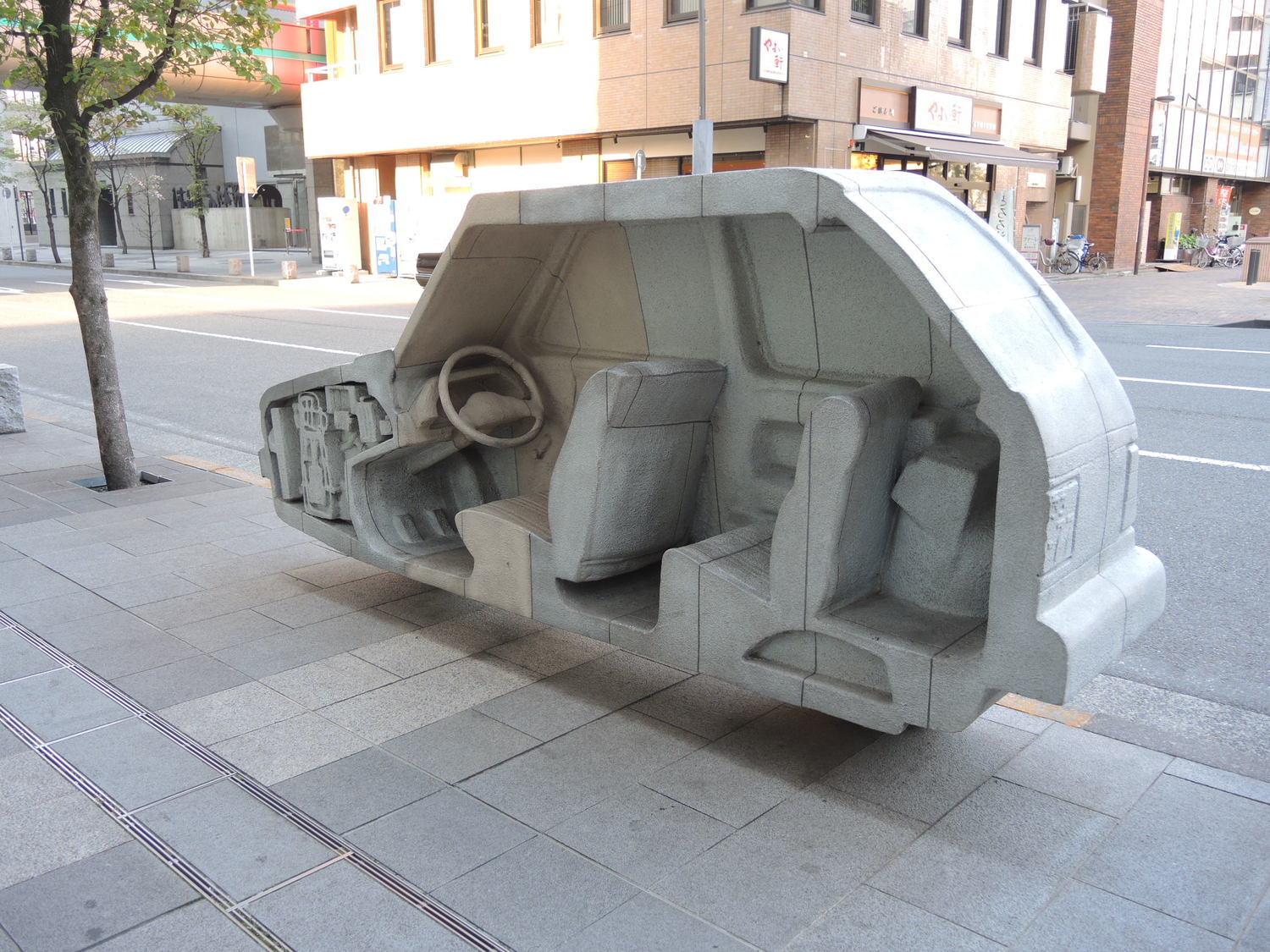

Meanwhile, the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennal has become quite a unique arts festival, even from a global perspective. There’s nothing quite like its format, which allows visitors to get into a car and roam Niigata’s vast area, around which are scattered enormous works of art. Visitors travel more distance between pieces than in any other arts festival in the world, and during their appreciation of the artwork, they are inevitably caught up in the enjoyment of the natural landscape. The event is not under the administration of the country nor the prefecture, but instead supported by Fram Kitagawa and the Art Front Gallery. Accordingly, though ordinarily arts festivals have a change of director each time, the Echigo-Tsumari Triennal has kept Fram Kitagawa at the helm for the six times it’s been held so far. It is also not the type of festival whose theme changes considerably each time, but rather, its sense of place possesses overwhelmingly strong meaning, as we come into contact with contemporary art within the scenery of the countryside, away from urban areas. Naturally, the area is not the kind that would have an art museum to begin with, and so empty houses, closed schools, fields and the like become the sites for the installation of artwork. It is an event that may not have been possible if Japan had had an increasing population and high economic growth. But precisely because rural areas are experiencing depopulation and declining birth rates, art has surfaced, with perfect timing, to fill that gap.

In any case, the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale, an unusual type of arts festival worldwide, became a huge hit, and many Japanese people have come to recognize it as a fine example of arts festivals and contemporary art. Incidentally, the first time I visited the countryside in Niigata, a certain scene came to mind. It was Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s Umbrellas project. 3,100 umbrellas were planned to be opened in both Ibaraki Prefecture, Japan, and California, USA, in 1991. I was an undergraduate in university at the time, and I went with friends in a car on a field trip to see the huge blue umbrellas set up in the rice fields. Regardless of scale, for works of art to exist within the landscape may not be so unusual anymore for today’s students, but at the time, it was a ground-breaking experience. The Art Front Gallery, represented by Fram Kitagawa, was the supporter on the Japan side of this grand project. They also run Faret Tachikawa (est. 1994), a project which has set up over 100 pieces of public art by artists from 36 different countries around Tachikawa Station. Thinking about it now, I believe this kind of project is connected to the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale, whose artwork has jumped forth, out from the art museum.

*All photographs have been taken by the author

(April 22, 2016)