The Significance of Diverse Audiences Enjoying Cultural Programs Together

There are now less than three years until the Tokyo Olympics and Paralympics begin. What kind of art scenes will exist three years from now? As a Deaf person, I can’t help but be very excited: there will probably be so many cultural programs carried out, and it appears that they will be organized so that all kinds of people will be able to participate.

In “Aiming for Culture-Based National Development with 2020 in Mind” (the “Kyoto Declaration”), released at the World Forum on Sports and Culture in October of last year, one finds the following:

The Olympics and Paralympics are also a culture festival. With 2020 in mind…our country will promote the cultural and artistic activities of people with disabilities, including perspectives that aim to create an inclusive society…. So dreams and hope can be shared via the participation of the whole nation, in the Tokyo 2020 Cultural Olympiad and Beyond 2020 program, affiliated individuals will come together and join forces with everyone in Japan to promote as cultural programs efforts to create a legacy that is rich in local flavor and diversity.

With Japan having declared that “dreams and hope can be shared via the participation of the whole nation,” including people with disabilities, I have been noticing that necessary measures to do so are gradually being put in place. For example, the Basic Act for Culture and Arts, which went into effect in June of this year, calls for the participation of people with disabilities in culture and the arts in Article 2 and elsewhere. In order to make this act effective, there is a need for concrete measures to be proposed.

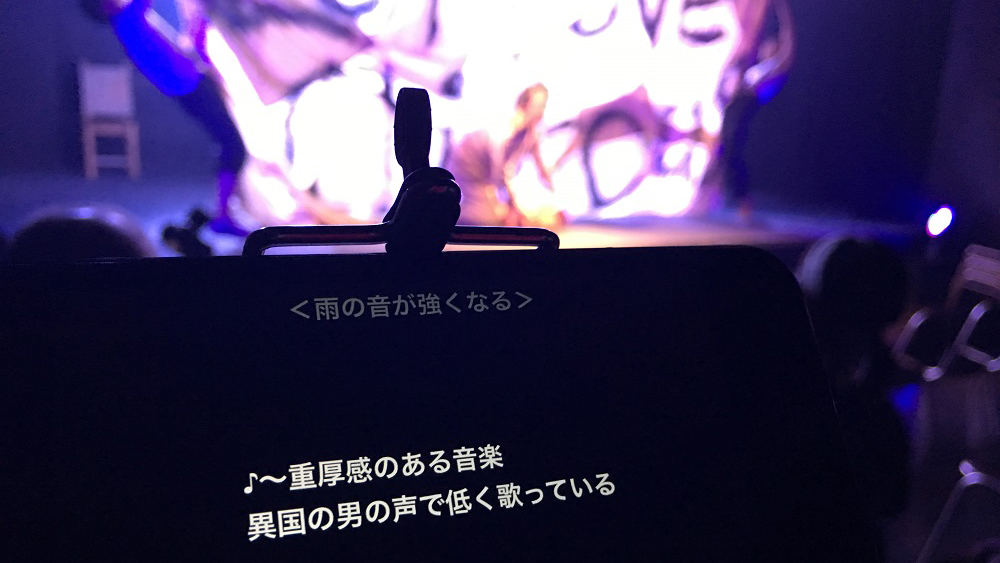

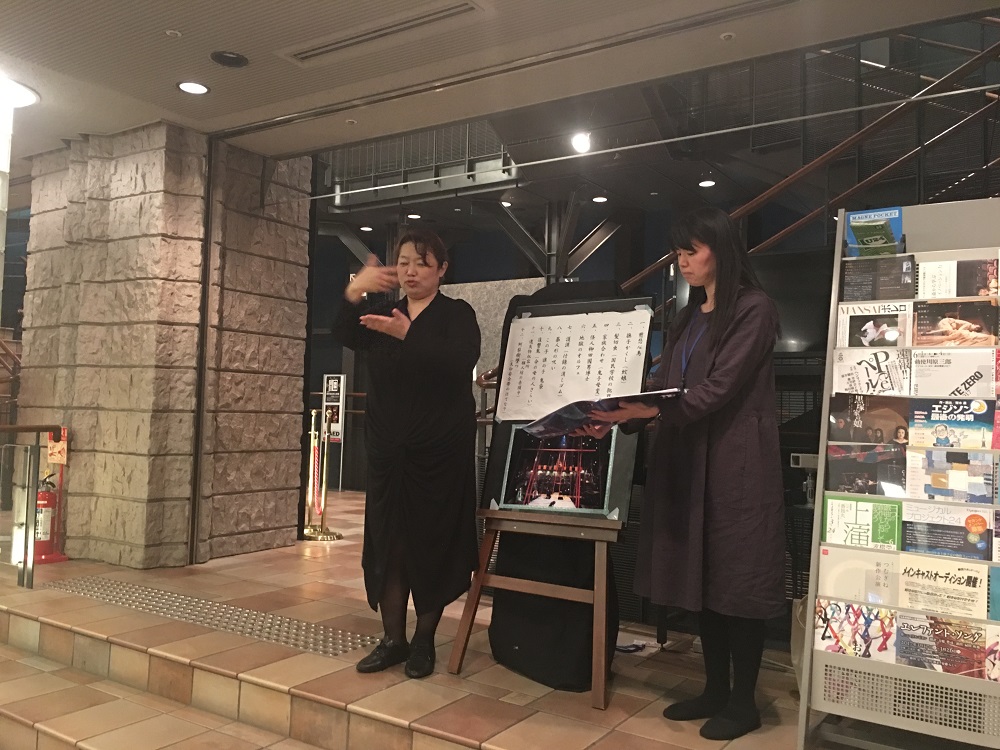

What, in the first place, is theater-going support? While it has often brought to mind the installation of wheelchair seats, it also includes captioning, sign language interpretation, the installation of a hearing loop, audio descriptions, the installation of stage models, and set explanations. They are considerations made by theaters and organizers for deaf, deafened, hard of hearing, and visually impaired theatergoers, for who it might be hard to understand performances without such assistance. Recently one also finds efforts to provide support for people with autism spectrum conditions, learning disabilities, and other sensory and communication disorders. These are nothing particularly special—in Great Britain and the United States, they are a matter of course, and many people with disabilities readily go to theaters for pleasure.

However, in Japan these activities are only carried out by good-willed volunteers, or by theaters while trying to manage a limit budget. For this reason, there are considerable obstacles faced by theaters and organizers that want to have diverse audiences at their shows. People with disabilities cannot regularly go to theaters because no support is provided. Even if it is, there are few opportunities to find out about it. As a result, they do not go often, and theater-going support ends up having poor “cost performance.”

In order to break through this situation, the Theatre Accessibility Network (TA-net) was launched at the end of 2012 under the slogan “Enjoying the Stage Together.” It became an NPO in July 2013. In the four years since then, while engaging in practice-based theater-going support research, TA-net has worked to exchange information and opinions through the connections it has formed with organizers, theaters, performers, theater fans, associations of people with disabilities, and theater-related groups. Also, it has engaged in activities to share the pleasure of theater with people with disabilities, using videos, panel displays, and so on. At its symposium held in March of this year, it released “Towards the Construction of Theater-Going Support Systems Open to Diverse People: 10 Proposals.”

In order to make these proposals a reality, I recently had the opportunity to share my opinions regarding accessibility-related issues as a member of an expert committee part of the Cultural Commission’s 15th Cultural Policy Section Performing Arts Working Group. I proposed that, just as stage work is carried out by stage staff, theater-going support be provided not by volunteers but professionals, and noted that in order to do so it is important to create an environment in which people can receive a professional education as such and financial support for involved expenses is provided.

While I do not know the extent to which my opinion will be able to be integrated into the committee’s policy—as of this article's writing, it is still under discussion—I think that it is very significant that a person with a disability like myself was appointed to a committee involved not in disability policy but art and culture. They included sign language and text-based interpretation for meetings, and other committee members accepted with understanding the changes made to the meeting format for me. It was an excellent and moving example of how to create an inclusive society.

Currently, people with disabilities tend to be excluded from cultural events. Even if this does not happen explicitly, they feel that they are not being actively welcomed and that such events are not environments in which they would feel comfortable. If these and other measures were implemented to provide high-quality theater-going support, audience members with disabilities would be able to fully enjoy quality cultural programs while feeling at ease. While an understanding that approaches theater-going support as a cost turns it into a burden and can lead to exclusion, if it is widely seen as just being part of the expenses needed to offer richer cultural environments and necessary preparations are made, then some audience members with disabilities who attend performances will surely become artists, giving rise in the future to a variety of artworks and wonderful art scenes throughout Japan.

Imagine a diverse audience in the same space enjoying the same play at the same time, crying and laughing together. They would share their impressions with each other on the way home, and turn their experiences into power for tomorrow. Children who attend plays with auditorily and visually disabled audience members—using subtitles, sign-language translation, or audio guides—and others sitting in wheelchairs would accept such situations without any second thoughts and grow up into people who work to create an inclusive society.