The Meaning of the Tokyo 2020 Cultural Program, Re-Questioned by Novel Coronavirus

I was asked to write an article looking back on the cultural program for the Tokyo 2020 Games. Although I took it on...what should I say? To be honest, I'm apprehensive.

It was February 2014, eight years ago, when I wrote an article entitled "Bringing Cultural Festivals to the Tokyo 2020 Olympic & Paralympic Games: To Present the World with a New Model for Fully Developed Countries" *1 for Net TAM. Since then, the cultural program was actually prepared and implemented, but the overall picture became extremely complex and diverse.

*1: Mitsuhiro Yoshimoto, "Bringing Cultural Festivals to the Tokyo 2020 Olympic & Paralympic Games: To Present the World with a New Model for Fully Developed Countries" Net TAM Course Special Lecture

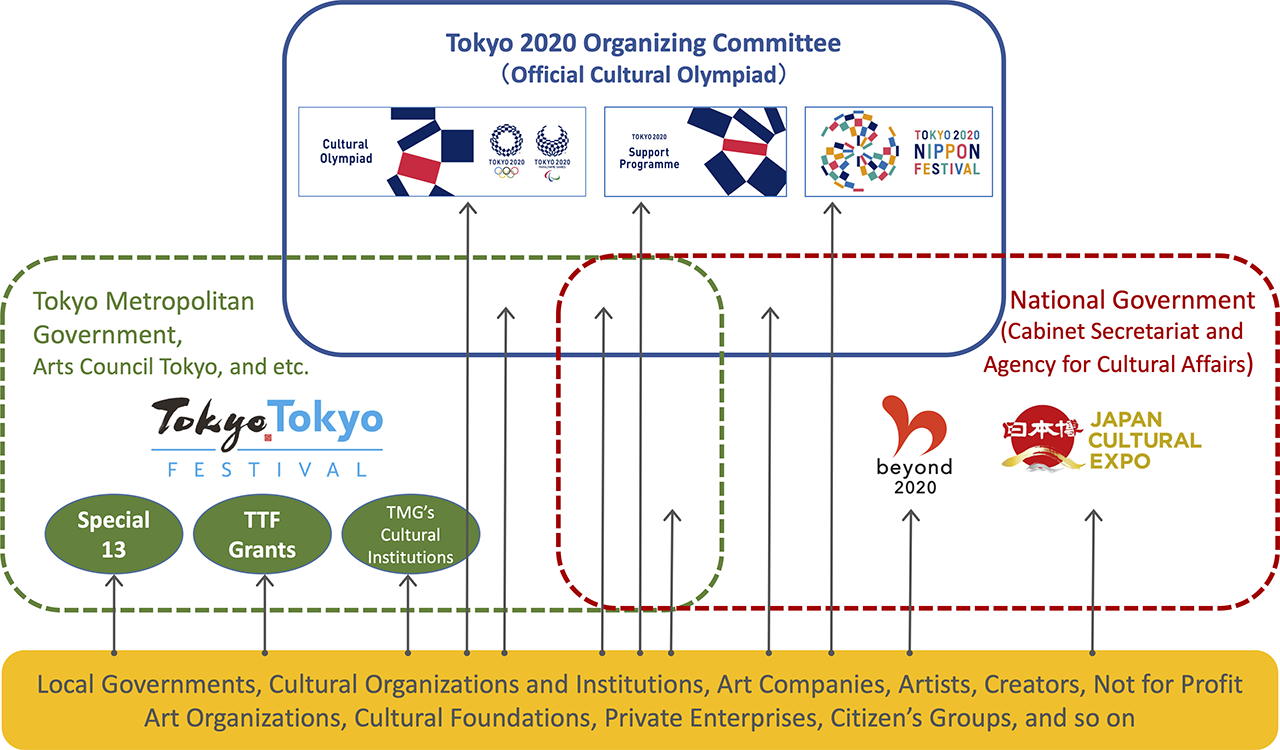

The three promotional bodies for the Tokyo 2020 cultural program were the Organising Committee, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government, and the national government (Cabinet Secretariat and Agency for Cultural Affairs). Although there was cooperation between these organizations, overall unification was not achieved, and as a result, each used their own logo, and as shown in the diagram, the structure became complicated.

Of these, the official cultural program included the Tokyo 2020 Cultural Olympiad Official Programme and the Tokyo 2020 Cultural Olympiad Support Programme, certified by the Organising Committee, and the Tokyo 2020 NIPPON Festival, hosted and co-hosted by the Organising Committee. The Tokyo Metropolitan Government developed a variety of cultural projects under the name of Tokyo Tokyo FESTIVAL, with a framework which included programs forming the basis of cultural promotion, carried out by metropolitan cultural institutions and other organizations, TTF grants to assist private organizations, and new symbolic projects, such as the Special 13 (described later).

The national government (Cabinet Secretariat, Agency for Cultural Affairs) prepared a certification system known as the beyond2020 Program, which would contribute to the creation of legacy from 2020 onwards, and promoted the Japan Cultural Expo with its comprehensive theme of "Humanity and Nature in Japan". The Agency for Cultural Affairs has also built and been operating a site called Culture NIPPON, which introduced the cultural program nationwide as a platform for cultural information.

The frameworks established by these three promotional bodies overlap one another, and there also many projects which span multiple frameworks.

Source: Author (logos referenced from the websites of each host organization)

Note: For the purposes and conditions for certification for each project (excluding the Japan Cultural Expo), please refer to my article, "2020. A Cultural Festival for the Entire Country" (NLI Research Institute Report, March 28, 2018). (in Japanese)

It's not that I was particularly interested in the Olympics itself in the first place. In 2005, former Tokyo Governor Ishihara announced the bid for the 2012 Olympics. From the following year, I became involved as an expert committee member in cultural policy of Tokyo Metropolitan Government, and learning that a cultural program would be held in parallel with sports games in Olympics piqued my interest. The deciding factor was my meeting Jude Kelly, then Chair of the Culture, Ceremonies & Education Advisory Committee for the London 2012 Games.

In 2007, she visited Japan at the invitation of the Japan Foundation, and held a talk session at the British Council. That was when, as a moderator, I asked her about the cultural program for the London 2012 Games. Contrary to my expectations that they might have been planning a spectacular cultural event which would contribute to British branding, Kelly began to talk about the thoughts and ideals that Coubertin had had for the Olympics. Their cultural program held a profound hope that went beyond the dissemination of British culture *2.

*2: For details, please see the "The potential of barrier-transcending art", Wochi Kochi (No. 18, 2007), Japan Foundation.

In February of the following year, she was invited to the Tokyo Council for the Arts as a guest, where she stated the purpose of the Olympic bid as follows.

In sympathy with Baron de Coubertin's ideas, we invite the Games because we have an impossible dream we want to make happen.

This means participating in his original concept, a mission to integrate sports, culture, and education in order to raise humanity. The Olympics is the only festival of humanity. It is not a sporting event. When you see it on television, you may think it's just for TV program, money, an awards ceremony — but it isn't. It had a larger, more profound purpose. It is time to show that it is about humans, why we should love humans, why we should care about humans.

Because this speech has been translated into English from the Japanese record, it may differ from Kelly's original speech in English.

In 2012, I visited London during the Olympics, and actually observed the cultural program *3。After repeated exchanges with related parties following that, in February 2014, a forum was held, inviting three core members who had promoted the cultural program of the London 2012 Games to Tokyo *4. They are Ruth Mackenzie (then Director, London 2012 Cultural Olympiad), Justine Simons (then Head of Culture, Mayor of London's Office) and Moira Sinclair (then Executive Director, London and South East, Arts Council England).

*3: For more information on the London 2012 Games, please see the following reports.

・Mitsuhiro Yoshimoto, "Cultural Festivals, London Olympics—Toward the Tokyo Olympics 2020" NLI Research Institute Report (September 5, 2012) (in Japanese) ・Mitsuhiro Yoshimoto, "The London 2012 Games—How was the Cultural Program Expanded Nationwide?" Regional Art Activities magazine (March 2016) (in Japanese)

*4: Open Forum: Sharing the Legacy from London 2012 – Tokyo 2020 (organized by: Arts Council Tokyo, British Council; planning partner: NLI Research Institute) ・Website

・Report (in Japanese)

Since then, whenever I have the opportunity, I have advocated for the Olympic Games to not only be a celebration of sports, but also culture. It was not uncommon for me to be invited to speak by local governments and economic organizations nationwide. What is the Olympic cultural program, what has its history been thus far, how wonderful was the London 2012 Cultural Olympiad, what should we expect from the Tokyo 2020 cultural program....

What I emphasized in these talks were two things: that the cultural program is not to be implemented for the Tokyo 2020 itself alone, but for each region and its future, and that excessive expectations for inbound tourism due to cultural dissemination should be avoided.

The cultural program began after the Rio 2016 Games. I was also involved in the cultural program for Tokyo 2020 as a core member of Organising Committee's Education and Cultural Committee, and as a chair of Tokyo Metropolitan Government's promotion committee of the cultural program.

Just before the full-scale program was about to be rolled out from April 2020, it was decided to postpone the Tokyo 2020 Games for a year due to the spread of COVID-19. The cultural program was also forced to postpone or cancel. Then, all of society became caught up in novel coronavirus. While it is said that culture and art are nonessential and nonurgent, the circle of support for culture from the national government, local governments, and the private sector expanded.

From then on, the cultural program for the Tokyo 2020 Games was focused more on how to realize it during the coronavirus pandemic, rather than on its vision and goal. Artists and involved parties racked their brains to implement the program in a form as close to their ideals as possible with repeated review, making the switch to online or continuing with implementation with infection prevention measures in place.

To avoid crowding, public relations activities were constrained (even those held outdoors), which limited the number of spectators to whom the cultural program could directly convey its message. Even so, I believe that the fact that the cultural program was completed even with ongoing COVID-19 situation is a huge achievement and accomplishment in and of itself. If it weren't for the cultural program of the Olympics and Paralympics, I'm not sure this much could have been done.

Since the spring of 2020, artistic activities have been forced to stagnate. Artists and cultural workers have lost their jobs, and opportunities for performances and exhibitions have been severely limited. Under such circumstances, not giving up on the Tokyo 2020 cultural program should have been a positive message to artists and people engaged in culture.

There were also discoveries, such as the creation of new methods of appreciation and experience by incorporating the Internet and AR. They're not exactly the same as real events when held online, but it makes it possible to reach the overwhelming majority of people across borders and time zones. A program hosted online by the Organising Committee was said to have been viewed live by more than a million people in Japan and overseas. A normal live event may have taken in around 10,000 audience at most.

Rediscover Tohoku – MOCCO's Journey from Tohoku to Tokyo

At the Tokyo 2020 NIPPON Festival, three major projects were implemented as part of the program hosted by the Organising Committee. Of these, two were streamed online, but this project, under the theme of the reconstruction of Tohoku from the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011, was held outdoors.

The aim was for Mocco, a giant puppet entrusted with a message from the people of Tohoku, to spread the word of the current state of Tohoku to both Japan and the world from venues in Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima Prefectures, while traveling to Tokyo. Unfortunately, the only venue at which it was possible to hold with an audience was in Rikuzen-Takata, Iwate Prefecture (at Takata Matsubara Tsunami Recovery Memorial Park) on May 15th. The events in Iwanuma, Miyagi Prefecture (Millennium Hope Hills Ainokama Park), and Minamisoma, Fukushima Prefecture (Hibarigahara Festival Site (Soma Nomaoi Festival Site) were unattended, open only to the press.

The event held on July 17th at the Japanese Landscape Garden in Shinjuku Gyoen, Tokyo, was also unattended, but was broadcast live online, and viewed by about 1.02 million people from Japan and overseas.

Since these events were unattended, with the exception of Rikuzen-Takata, only a limited number of people were actually able to see Mocco, the giant 10-meter-tall doll, which was the symbol of this project (even in Rikuzen-Takata, the number of spectators was kept to about 600 to avoid crowding). When I think of what a memorable experience it would have been for many children to see Mocco walking, dancing, and looking at them, I can't help but feel disappointed.

Mocco was completed as a work by Noriyuki Sawa, a world-famous puppet theater artist, with the base design created by picture book author Ryoji Arai, based on designs drawn by children from disaster-affected areas at a workshop held by Masato Nakamura and Shinji Omaki, professors at Tokyo University of the Arts.

In Tokyo, the song "Tohoku-no-Sachi (Happiness of Tohoku)", which was written from the messages of many people toward the reconstruction of Tohoku, was performed, with singing by Sayuri Ishikawa and rapping by Mummy-D. The program encompassed the thoughts and wishes for the reconstruction of Tohoku of many people involved in the project, including Michihiko Yanai from Fukushima Prefecture, who worked on the overall production as the Creative Director.

Mocco performing at Shinjuku Gyoen National Garden

Photo: Author

As for the co-hosted program of the Tokyo 2020 NIPPON Festival, of the 32 projects planned, six were cancelled due to the impact of novel coronavirus, and 26 were implemented.

Meanwhile, there were many projects that left strong impressions on those who witnessed and experienced these cultural programs, even if their numbers were limited. In fact, at the Tokyo Tokyo FESTIVAL Special 13, many messages were posted on social media expressing their joy, surprise, and appreciation at seeing the work. For example, in response to Makoto Aida's Tokyo Castle at Pavilion Tokyo 2021: "I think it's great they did it here. Tokyo hasn't been tossed aside just yet," as well as in response to Tadanori and Mimi Yokoo's Super Wall Art Tokyo: "The art based on the theme of water and fire felt so extraordinarily powerful, even from a distance."

In 2018, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government and Arts Council Tokyo held an open call for projects, soliciting a wide range of innovative and original projects from artists and creators: projects that could only be done with the Olympic Games, and projects that many people could participate in. If a project was adopted, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government would grant a consignment fee, up to 200 million yen (approximately 1.7 million USD) per project. 2,346 applications were received from within Japan and overseas (114 projects from 28 countries/regions: 74 from Europe, 16 from the Americas, 11 from Asia, 7 from Oceania, and 6 from Africa). As a result of the screening process, thirteen projects including proposals from the UK and Argentina were adopted and implemented as the Tokyo Tokyo FESTIVAL Special 13.

One of the most talked about was masayume (which literally means prophetic dream), by contemporary art team [mé]. Faces were solicited from all over the world, and from more than a thousand faces that were gathered, "one real face" was selected and set afloat in the Tokyo sky. Its size was about six to seven stories high, and it rose up in Yoyogi on July 16th and along the Sumida River on August 13th. Unfortunately, due to weather restrictions, the time it was allotted to float was limited, but it left a strong impression on those who witnessed it.

Floating in the sky above Yoyogi

[mé], masayume, 2019-2021, Tokyo Tokyo FESTIVAL Special 13

Photo: Takahiro Tsushima

While many of the cultural projects held were meant to enliven the Tokyo 2020 Games from a cultural aspect, [mé] stated that this project was not one which focused on that, but was absolutely a work of art. Without any prior publicity, what would someone feel or think if they happened to see a huge face floating in the sky?

In a press release (August 13th, published by the Arts Council Tokyo and Masayume Project Office), the following text was written as key words and phrases which the artists wanted to convey: "The overwhelming "other" seen around the world: the huge face floating in the sky that can be seen from all around the world through social and traditional media is the "other" to people worldwide. What is the "other" we see in this generation, in these circumstances? How much can we think about others?"

Other key words and phrases included "the scene of a ‘mystery' that has appeared", "the concept of ‘individual' and ‘public'", and "art is ‘to see this world once more'", but there isn't a definite answer. It was an artwork that asked such big questions to each person who witnessed it.

Other large-scale projects were developed within the city, including the Pavilion Tokyo 2021, in which eight architects and artists active around the world created as their own pavilions around the New National Stadium, as well as Super Wall Art Tokyo, in which the walls of the Marunouchi Building and Shin-Marunouchi Building in front of Tokyo Station were used as canvases to display huge murals about 150 meters high and 35 meters wide, created by Tadanori and Mimi Yokoo.

Tokyo Castle by Makoto Aida, installed at the Gingko Avenue entrance of Meiji Jingu for Pavilion Tokyo 2021

© AIDA Makoto

Photo: ToLoLo studio

Many of these TTF Special 13 projects were held in outdoor spaces where cultural events had never been held before. I hear that there were a number of obstacles to overcome in addition to preventing the spread of novel coronavirus, including finding venues in consideration of safety and viewing environment, providing explanations to and obtaining permission from related parties in advance, and responding to various regulations, etc. I hope that the experience of overcoming such difficulties in making artwork and projects a reality will have a positive effect on future cultural policy in Tokyo.

The phrase "Olympism...[blends] sport with culture and education", from the Fundamental Principles of the Olympic Charter, has often been introduced as the basis for the cultural program. In fact, after that, it continues: "Olympism seeks to create a way of life".

The global COVID-19 pandemic has made this fundamental principle even more meaningful. This is because the social and economic systems that humanity has built thus far are now unstable; changes in values and behaviors have become urgently necessary, and the creation of a new way of life is exactly needed.

Why does our society need art and culture? Novel coronavirus has caused us to ask this question again. The pandemic is said to have advanced the division of society. But precisely because we are in such a difficult situation, art and culture should have the power to promote solidarity across borders, to restore a closed-off society, and bring vitality to people. This may also lead to the creation of a way of life as described in the Olympic Charter.

By carrying out the cultural program even while facing novel coronavirus and a variety of conflicts, artists, art organizations, organizers, and everyone involved must definitely have gained something. That has to be put to use in future artistic expression, in cultural projects, and in future cultural policy.

That is what should be the legacy of the Tokyo 2020 cultural program.