Beyond Confusion and Order: Tokyo, Rio de Janeiro and Tokyo again

The exhibition of "The Emergence of the Contemporary: Avant-Garde Art in Japan 1950-1970" (hereinafter called "The Emergence of the Contemporary" exhibition) was sponsored by the Japan Foundation and held from July 14, just before the opening of the Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro until August 28, when the Olympics finished and before the opening of the Paralympic Games. It was held in the Paço Imperial, an art museum located in the center of Rio and utilizing historical buildings. Paço Imperial was built in the 18th century as an official office for the governors of colonial Brazil and at one time also became an imperial building, as the residence of the Portuguese Royal Family.

Focusing on the Tokyo Olympic Games in 2020, the Japan Foundation implemented three cultural programs in Rio and the exhibition was one of the important pillars of those programs. As well as appointing as the curator the professor of Cornell University, Pedro Erber, who was born in Rio and lives in the United States as a researcher, we received advice on the selection of works from Katsuo Suzuki, a curator of the Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. Together with the staff from the Japan Foundation, myself included, a mixed team from Brazil and Japan took charge of the exhibition. With the two different perspectives of Japan and Brazil, it was a great challenge for this team to put together a multi-faceted exhibition and work out how the exhibition could produce some interest or understanding of Japanese Art in the Brazilian spectators who have little knowledge of postwar art in Japan. The theme of this exhibition was "Contemporary Art" in postwar World War II Japan, an area that Erber has repeatedly researched until now. In Japan that was finally recovering from the defeat of World War II and was trying to accomplish a remarkable reconstruction, how was "Contemporary Art" born and what kind of meaning did it have? This development would be verified by the exhibition. It was the first time for such an exhibition outlining post-war Japanese art history to be held in Brazil.

Photograph: Jaime Acioli

The exhibition consisted of three thematic sections in chronological order: "Politics of Abstraction", "Art and Social Engagement" and "Matter, Concept and Art". In "Politics of Abstraction" we introduced comparatively the works in "Hot Abstraction" by the Gutai group that represented Abstract Expressionism in the 1950s and Jikken Kobo, the group which boldly adopted the latest scientific technology at that time. In "Art and Social Engagement", there were displays from artists from various art movements from 50' to the Olympic Games in 1964, including Hiroshi Nakamura and Tatsuo Ikeda and other artists who were active in reportage painting that was closely linked to social movements of that time, as well as artists such as Genpei Akasegawa, Jiro Takamatsu and Natsuyuki Nakanishi, and even Yusaku Kamekura's posters for the Tokyo Olympic Games. In this section, news videos from the latter half of the 1960s and photographs and videos of the students' movement were on display and the display area was full of the feeling of lively dynamism characteristic of that era. In the final section, "Matter, Concept and Art", Yoko Ono represented Conceptual Art and, as well as Yutaka Matsuzawa, there were the photographs and concrete poetry of Mitsutoshi Hanaga, in addition to Tamio Suenaga's valuable footage and materials of the late 1960s, and the new works of Kishio Suga who was a representative figure in "Mono-ha", on display. As the hot era came to an end, gradually the focus turned to a stable expression of inner calm and the last section came to a quiet ending with the poetic and implicit works of Yutaka Matsuzawa, "My own death" and "Swan song".

Photograph: Jaime Acioli

Photograph: Jaime Acioli

Photograph: Jaime Acioli

Photograph: Jaime Acioli

In order to hold an exhibition in Brazil that is so far from Japan, there are many hurdles to be overcome, such as the long travel distance for the transportation of artwork (= high costs), concerns about the budget and infrastructure and time constraints. However, taking the opposite view of such a difficult situation, we focused on the theme of the exhibition and aimed to achieve an even more compact and powerful expression by using a limited number of high-quality works.

In addition to an introduction to Japanese postwar art, we decided that we should have contact with local art and artists through the exhibition and hold local performances that would be easy for the people in Rio to attend. The Tokyo Olympic Games in 1964 was the most impressive event for Japanese people after the war but we were able to reconsider how the Olympics and art were connected to each other in such a different and distant place as Rio. As a result, we thought that there was something that the two cities hosting the giant event of the Olympic Games could share over this period of 52 years.

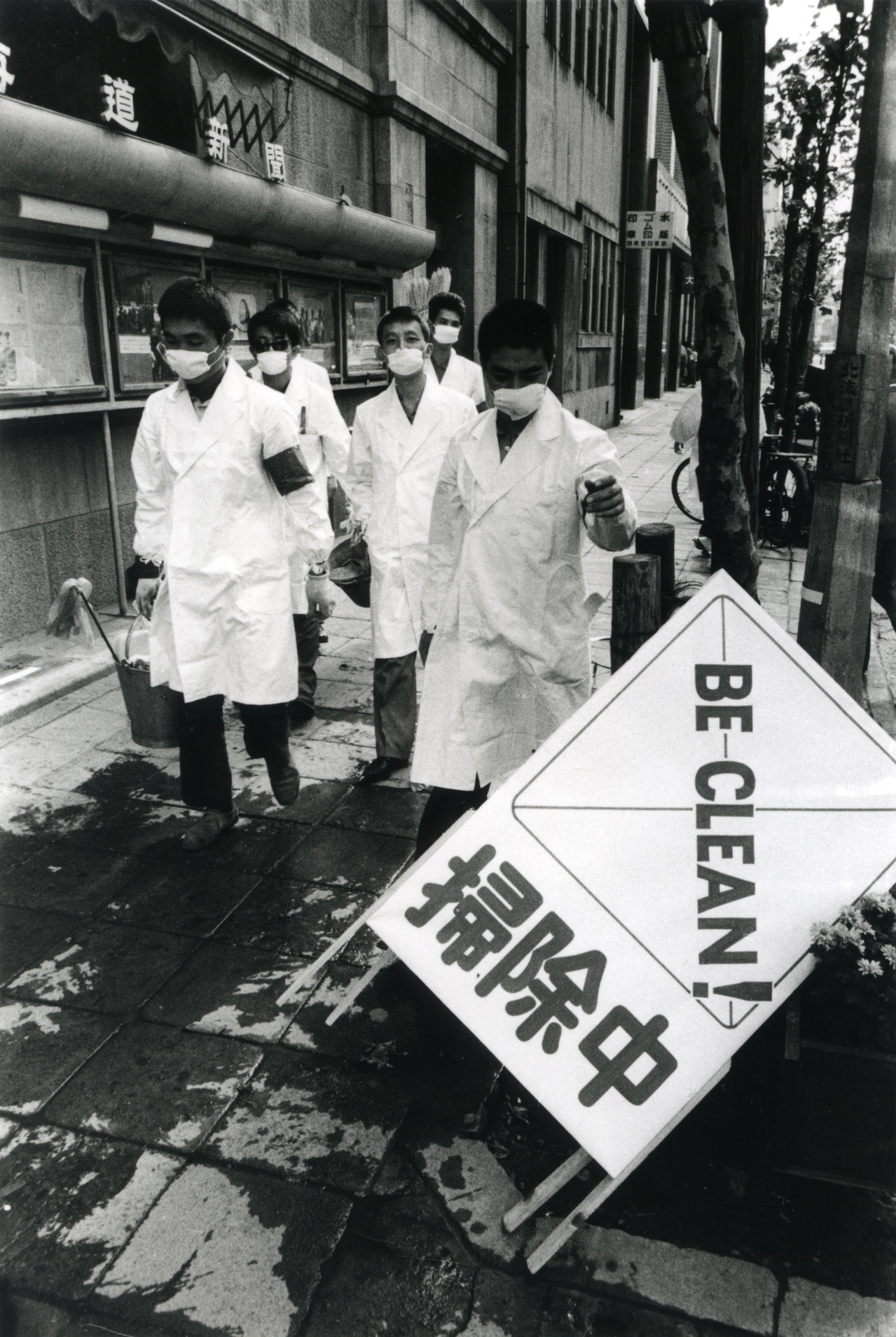

One of the performances was a new work based on the concept of the "Movement to Promote the Cleanup of the Metropolitan Area" from the Hi-Red Center (HRC) group composed of the three artists, Jiro Takamatsu, Natsuyuki Nakanishi and Genpei Akasegawa, a work that was commissioned to be performed by a young performance group based in Rio. This HRC performance that has become famous now through the photographs of Minoru Hirata and the statements of Akasegawa, was held on the streets of Ginza during the Tokyo Olympic Games. After the curator explained to the artists about the HRC performance in advance, only three conditions for the performance were given to them. To hold it on the streets of Rio, not to tell the people surrounding them that it was a performance and to refer to the Olympics in some way or other. This performance was given by the performance group living in Rio, Seus Putos. They had given before various performances in the political and cultural context of Rio, but this time they performed "clean up the streets" just like HRC in the streets near the art museum. The artists daringly selected the same actions as HRC for this "Operation Clean ALERJ" and the photos and videos taken of this performance were exhibited at the art museum. The gorgeous and colorful costumes worn by Seus Putos and their movements provided a good contrast with the monochrome photos of HRC wearing austere white coats.

Photograph: Jaime Acioli

(C) Minoru Hirata Courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery Photography/Film

The second performance was one that sought to consider "the city" and "urban space" from a broad perspective and was planned while referring to the citizen participation performance "Incubation Process" carried out in Tokyo by Arata Isozaki in 1962. Just as the development of Tokyo accelerated and the country became equipped with the Shinkansen and expressways at the time of the 1964 Olympics, the port area in Rio was developed, for example, including the opening of the "Museum of Tomorrow" in Rio in 2015, and heated discussions broke out in Rio, both for and against urban development. Cities are not managed and developed according to plans, instead they develop irregularly and in unexpected ways, just like amoeba, as a result of the intervention by humans. In this way, Isozaki's ideas were incorporated into the experiences of each one of the citizens of Rio who participated in the performance of hammering nails into the map of Rio with their own hands and winding wire around nails and walls and stretching it.

Photograph: Jaime Acioli

Photograph: Jaime Acioli

These performances were performed prior to the exhibition and stimulated many feelings of interest and understanding of the exhibition among the participants,even befor the opening of the exhibition.

In addition, I would like to mention the installation works made and exhibited at the Paço Imperial. As well as the exhibition works from Japan, we decided to commission two installation works in order to present to the audience in Rio new works that were specially made locally using Brazilian materials. One of the works was a new work commissioned to Kishio Suga, an artist representative of "Mono-ha" who started to be active around 1970. The pillar of his work was "Cultivation of Critical Spaces" that emphasizes the dialog between places and things using Brazilian wood and stone as materials and creating a powerful exhibit with its simplicity and roughness in the materials.

Photograph: Jaime Acioli

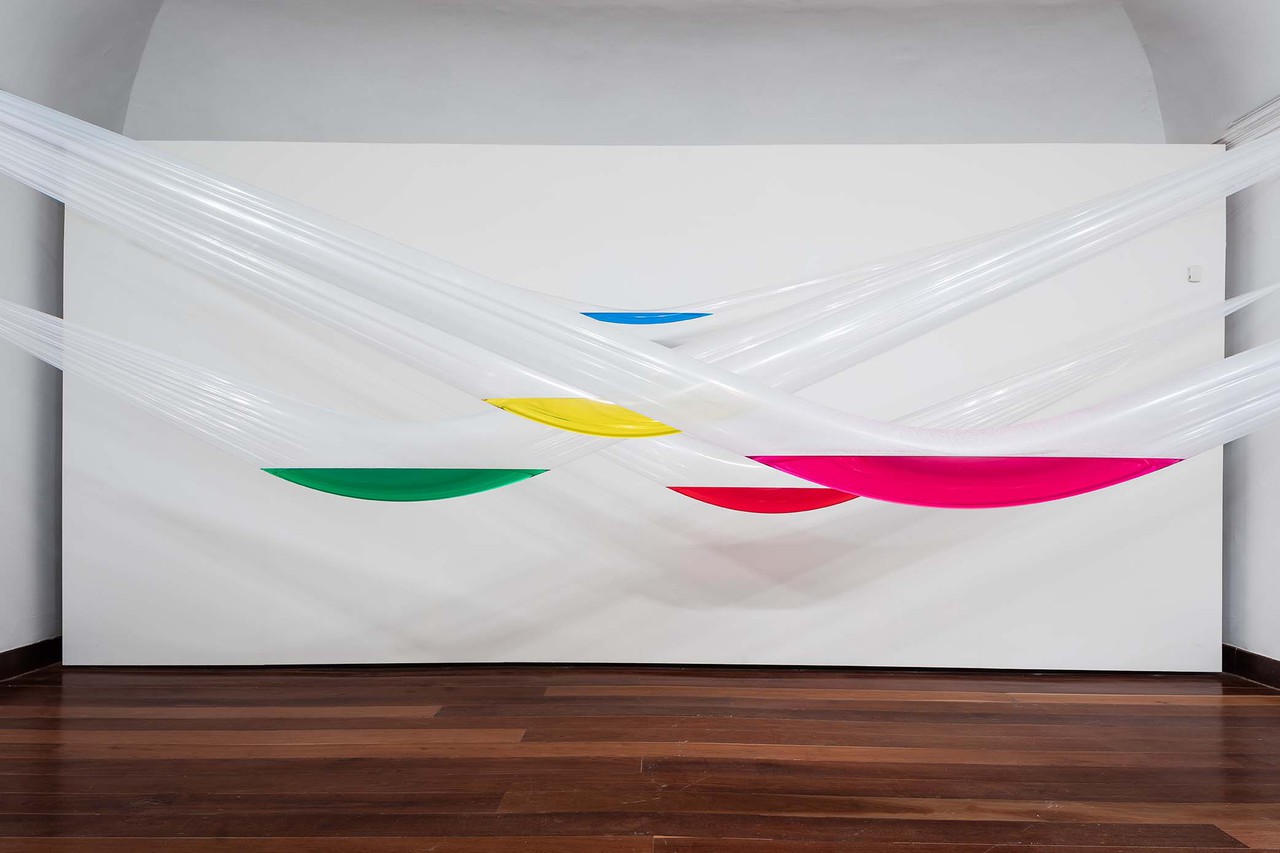

Another work is the outdoor installation "(Work) Water" produced by Sadamasa Motonaga in 1956. When the beautiful installation "(Work) Water" (1956/2016), with its high degree of perfection using water, was placed in the Paço Imperial venue, the impression given by the artwork was changed by the light shining through the beautiful 18th century wooden windows and the delight seen in the eyes of the visitors deserves a special mention here.

Photograph: Jaime Acioli

Finally, in regards to the success of the exhibition, the power and originality of Japanese Contemporary Art from 1950 to 1970 were fully demonstrated through the completely skillful employment of various media such as paintings, videos, documents, materials and three-dimensional structures. As a result, a large audience of over 36,000 visitors came to the exhibition which exceeded the prior expectations of the Paço Imperial Art Museum.

During the Olympic period, when a lot of space in newspapers was spent on the coverage of sports and political affairs, the exhibition was introduced in all of the major newspapers such as Sao Paulo's biggest newspaper "Folha de Sao Paulo" and in Rio's main newspaper "Il Globo" as well as in magazines and on television programs. So the fact that the exhibition received so much attention by the press clearly showed that local people who had little knowledge of Japanese history were attracted to the exhibition with a high level of interest. This is due to the power of the local media as well as the introduction of new performances and works that were an inspiration to mobilize an audience. Although the number of Japanese who visited this exhibition was limited due to the venue being in the distant location of Rio, visitors told us, "This is a precious exhibition that cannot be seen in Japan. We definitely want you to hold it in Japan as well." I want to treasure the miraculous opportunity given to me to hear these words.

There is the existence of collective memories and a shared unconscious of the people living in a city. Bearing in mind the memories of the Olympic Games in 1964, I wonder what kind of Olympic Games will be held in 2020 and what kind of memories will be left in Tokyo. I want to carry on watching Tokyo and Rio, with great expectations for the future of the two cities.

Photographs provided by: The Japan Foundation

November 7, 2016